오관진

페이지 정보

본문

작품설명

오관진 OH KWAN JIN(吳官鎭)계원예술고등학교졸업

홍익대학교 및 동국대 대학원졸업

개인전: 38회

초대전:

New York Gallery Jang, New York Kate Oh Gallery 3회 초대전, Feelapp Gallery 초대전, 비움과 채움갤러리 초대전, 북촌 한옥센터, 갤러리 두 초대전, 호텔28갤러리 초대전, 갤러리 쿱 3회 초대전, 갤러리 마레 초대전, 박영갤러리 초대전, 프랑스 대한민국 문화원(파리),베컨갤러리초대전(IBK한남동PB센터),갤러리포스초대전,장은선갤러리초대전,한원미술관초대전,알토아트페어부산(분산센텀호텔),매경-오픈옥션선정작가전(매일경제본사).명동갤러리초대전,부스개인전:(예술의전당6회),(단원미술관),파리라데팡스(신개선문),일본동경,화지갤러리초대전,종로갤러리2회초대전,라메르갤러리초대전,관훈갤러리,한선갤러리,시립미술관,공평갤러리초대전,벽강갤러리초대전)

그룹전:

키아프, 소아프, 베트남 아트페어, 싱가폴 아트페어, 마이에미 아트페어, 미국 뉴욕 국제아트페어, 이스탄불아트페어, 대구아트페어, 마니프 국제 아트페어, 화랑미술제 및 국제 교류전 280여회

수상 :

대한민국미술대전 특선,한국미술대전 우수상,마니프상.일본 국제선면전 장려상,아시아 미술대전 대상,경향하우징아트페어 대상

작품 소장:

하버드대학교, 오쿠라호텔(마카오), 프랑스 한국문화원, KBS 방송국, 국립현대미술관, SK그룹,동양제철화학그룹(OCI),파라다이스호텔그룹, 국회의사당, 호주 RMIT 대학교, 싱가폴 SOTA국제학교, 오뚜기그룹,경기도박물관,마재성지본당,한원미술관,수원대학교,고은미술관,동경화지갤러리, 한일 스틸, 병원 및 기업체, 개인 다수 소장. 콜라보: 삼성생명, 아모레퍼시픽, 한국인삼공사, 행복이가득한집, 오뚜기그룹

TV 방송사 드라마 협찬

2011년 KBS-1TV 낭독의 발견 추석특집 우주인 이소연씨와 출연

달과 달항아리에 대한 이야기 나눔(1시간)

2012년 SBS TV 주말드라마 ‘맛있는 인생’(임채무, 예지원, )

2013년 SBS TV 수목 드라마 ‘그겨울 바람이 분다,(조인성, 송혜교, 김범, 배종옥)

2013년 SBS TV 주말드라마 ‘돈의 화신’(강지환, 박상민, 황정음)

2013년 SBS TV 아침드라마 ‘당신의 여자’(이유리, 박윤재, 임호)

2013년 SBS TV 수목 드라마 ‘내연에의 모든 것(신하균, 이민정, 박희순)

2013년 SBS TV 주말드라마 ‘결혼의 여신’(남상미,조민수, 김지훈,이상우 이태란)

2013년 SBS TV 월화드라마 ‘황금의 제국’(고수, 이요원, 손현주, 장신영, 박근영)

2013년 KBS TV 월금드라마 ‘루비반지’(이소연, 김석훈, 임정은, 정애리, 박광현)

2013년 KBS TV 월화드라마 ‘총리와나’(이범수, 윤아, 윤시윤, 채정안, 류진)

2014년 KBS TV 월화드라마 ‘태양은 가득히’(윤계상, 한지혜,조진웅)

2014년 KBS TV 주말드라마‘참좋은 시절’(이서진,김희선,김지호)

2014년 SBS TV 월화드라마 ‘신의 선물’(조승우, 이보영, 김태우,정겨운)

2014년 SBS TV 주말드라마 ‘끝없는 사랑’ (황정음,류수영,정경호,차인표)

2014년 KBS TV 월금드라마 ‘고양이는 있다’(최윤영,현우,최민,전효성,독고영재)

2014년 KBS TV 금토드라마 ‘프로듀사’(김수현, 공효진, 차태현)

2015년 SBS TV 월금드라마 ‘돌아온 황금복(심혜진, 전미선, 전노민, 이혜숙, 신다은)

2015년 SBS TV 월금 아침 드라마 ‘어머님는 내며느리(김혜리, 문보령, 이용준, 오영실)

2015~2016년 MBC TV ‘내딸 금사월(백진희, 전인화, 손지창)

2016년 TVN ‘치즈인더트랩’(박해진, 김고은,서강준, 이선경)

2016년 KBS2 TV‘태양의 후예’ (송중기, 송혜교)

2016년 SBS TV 월금드라마 ‘사랑이오네요’(김지영, 고세훈, 나선영, 이훈)

2017년 SBS TV ‘귓속말’(이상윤. 이보영)

2017년 KSB2 TV ‘쌈마이웨이 (박서준, 김지원, 안재홍)

2017년 KSB2 TV ‘란제리 소녀시대’(보나, 채서진, 서영주)

2017년 SBS TV ‘달콤한 원수’(박은혜, 유건, 이재우)

2019년 SBS TV‘수상한 장모’(김혜선, 신다은, 박진우)

2021년 TVN TV ‘간떨어지는 동거’ (장기용, 혜리, 강한나)

*

< 평론 >

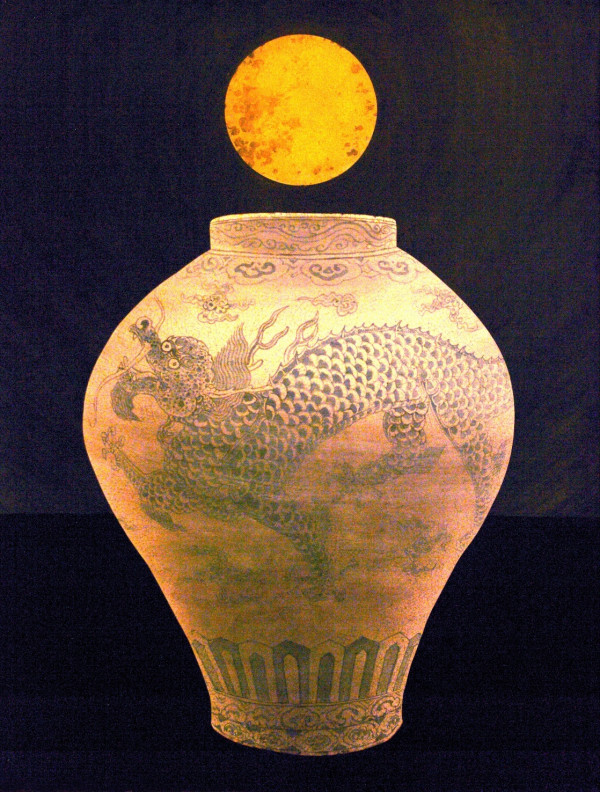

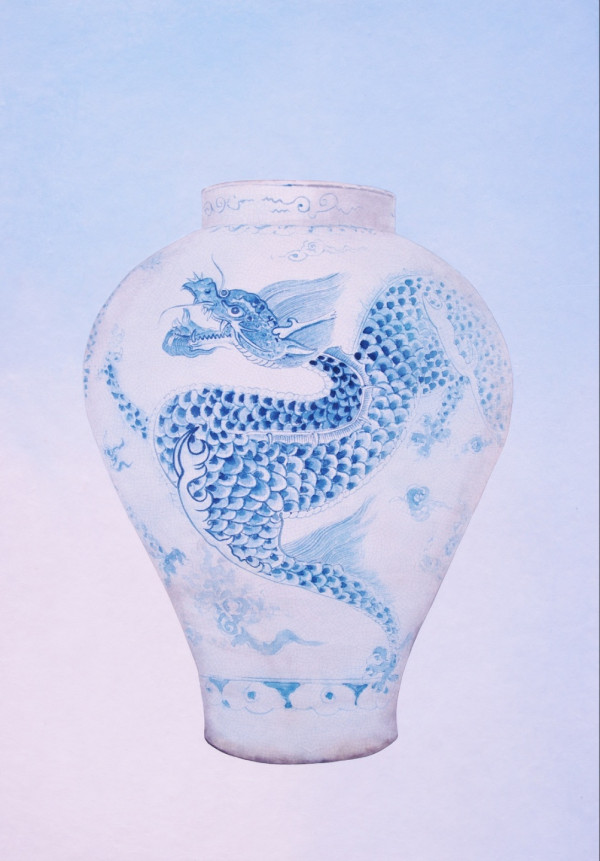

달항아리에 최초로 빙열을 그린 오관진의 작업은 오늘날 도자기에 빙열을 그리는 많은 작가들에게 깊은 영향을 끼쳤습니다.

작품을 자세히 들여다보면, 수많은 빙열이 화면 위에 세밀하게 그려져 있음을 확인할 수 있습니다.

오관진의 작업은 단순히 빙열의 외형을 묘사하는 데 그치지 않습니다. 그는 빙열이 지닌 철학적 의미와 시간의 흔적, 자연의 섭리를 달항아리 위에 담아냄으로써, 전통적인 오브제인 달항아리를 현대미술의 언어로 재해석하는 데 성공했습니다. 그의 작품 속 빙열은 마치 오랜 세월을 견뎌온 도자기의 생애를 닮아 있어, 관람자로 하여금 깊은 사유와 감정을 불러일으킵니다.

이러한 오관진의 독창적 시도는 이후 전통 도자기를 주제로 작업하는 수많은 작가들에게 직·간접적인 영향을 미쳤습니다. 그 결과, 빙열은 단순한 장식을 넘어 회화적·조형적 요소로 확장되었고, 이는 동시대 작가들의 작품에서 빙열이 적극적으로 활용되는 사례들로 확인되고 있습니다.

결과적으로 오관진 작가는 도자기 빙열이라는 자연스러운 흔적을 현대미술의 중요한 언어로 끌어올리며, 도자기 회화의 새로운 지평을 연 작가로 평가받고 있습니다.

☆오관진 작가의 작업은 전통성과 현대성이 만남.

1. 미니멀리즘(Minimalism)

비움과 채움의 철학, 달항아리의 단순한 형, 여백의 미는 미니멀리즘의 핵심 개념과 닿아 있습니다.

특히, 시각적 과잉을 지양하고 본질로 돌아가려는 태도는 도널드 저드(Donald Judd)나 아그네스 마틴(Agnes Martin)의 작업과도 철학적으로 연결됩니다.

2. 와비사비(Wabi-Sabi) – 일본 미학이지만 동아시아 전체와 관련

빙열은 시간의 흐름과 자연의 변화, 그리고 불완전성을 시각화한 요소입니다.

오관진의 빙열 표현은 '완전함 속의 불완전함'이라는 와비사비 철학과 유사하며, 이를 통해 존재의 덧없음과 아름다움을 동시에 드러냅니다.

3. 시간 기반 예술(Time-based Art)

비록 정적인 회화이지만, 그의 빙열 표현은 시간의 흔적을 시각화한 것으로 볼 수 있습니다.

마치 시간이 지나며 생성된 균열을 되살려 그리는 과정은 '시간의 기록'이자 '시간의 재현'입니다.

이는 설치미술이나 퍼포먼스의 '시간성'과도 연결될 수 있습니다.

4. 리추얼 아트(Ritual Art) & 퍼포먼스 아트

최근 뉴욕 전시에서 선보인 비움과 채움 퍼포먼스는 전통 도자의 ‘신성함’과 ‘의례성’을 현대적으로 해석한 예입니다.

달항아리를 내려 도려내는 행위는 단순한 시각예술을 넘어, 의식과도 같은 행위 예술로 기능합니다.

5. 하이브리드 정체성(Hybrid Identity)

전통 도자기라는 오브제를 서양 회화 문법으로 재해석한 작업은, 서양과 동양, 과거와 현재, 회화와 조각 사이의 경계를 넘나드는 하이브리드 미학을 보여줍니다.

호미 바바(Homi Bhabha)의 이론처럼, 경계 지대에서 새로운 문화가 탄생한다는 제3의 공간(The Third Space) 개념으로 해석할 수도 있습니다.

*

Kwan Jin Oh’s “Emptying and Filling”

3 ~20 Jan 2023

Kate Oh Gallery in New York

The “moon jar” is a distinctive type of porcelain vessel from the late Joseon period (1392– 1897). The moon jar (viz., dalhangari) is so called due of its form, which was traditionally made by adjoining two hemispherical halves. The joined halves often come to evoke full moons themselves, beaming and blossoming into a mereological whole more sumptuous than their disparate pieces. Kwan Jin Oh's "Emptying and Filling", brimming with paintings of moon jars, is unique for myriad reasons, not least of all the jars’ speckled, toothed chips of paint. This is a notable painterly technique worthy of some analysis à la art history. Consider the extant 16th century Cranach workshop renderings of the Judgment of Paris, each of which similarly contain such ripples of dappled paint squares—these have been earned over time, with art restorers choosing to allow the works to age, chronicling their years. When we look at such works, we are immediately, affectively, and resolutely aware of their status as aged vehicles. But Oh’s paintings, themselves, are new, the earliest painting in this series from 2017. This being a painterly penchant to impute the adorned vessels with a kind of wisdom beyond the medium’s intrinsic nature, Oh has chosen to remind us that the moon jars are relics. The ceramic jars are alighted with life: they appear to swell and heave in these paintings. The vessels are truly expertly painted, the blush-auburn handles adumbrated against a flat, light-teal foreground. Oh also employs myriad techniques in his works, bringing representational figuration into conversation with abstraction. An impressionistically painted series of bright, pink buds swoop in serpentine fashion, a charcoal-dotted branch disappearing against a bright white orb to the upper right of the canvas. The moon metaphor is here doubled, but stylistically the artist has chosen to give us dimensionality on the one hand and flatness on the other. Oh’s use of flatness against veridical dimensionality truly distinguishes him from contemporaries who so often veer from poetic whimsy and indulgence.

The moon jars threaten to jump out of the canvas, almost photo-realistically painted. There is no question that Oh has proven himself as a talented artist, beyond capable of producing verisimilitude. Hence why going beyond mere studies of jars and artifacts into poetry is the next challenge, and one that the artist meets with fortitude. In one of my very favorite works, two azure birds are perched on the base of the ceramic piece, a twig branching out, their beaks folding into one another. The birds appear to be at play. This could almost be a study of birds copied from nature, as the details of every element are incisively captured. But then the birds are refracted onto the cracked moon’s sun-lit body, prodding us out of the world of figuration and into the media-at-hand: the world of the vessel. For it is, indeed, the vessel that is the central motif in Oh’s works, and these vessels are where the aforementioned cracks and teethed tatters ripple. This repeated choice to return to the being of the vessel means that Oh is not feigning aged paintings beyond their years, imitating the wilting of 16th century Cranachs, but examining how artifacts’ being aged anchors their historical sonority. Just as figuration and abstraction are dovetailed, antiquities and contemporary motifs are brought into a mutual relation.

In his recent excellent New York Review of Books review, "Between Abstraction and Representation", Jed Perl, by my lights one of the numbered genuinely brilliant living art critics, notes that artists like Julie Mehretu have recently attempted to bring elements of abstraction into play with figurative elements, albeit without committing to either mode with vigor. Often, any meaning such “abstract-cum-figurative” works impute requires exegetical intervention—perhaps a title which tells us that Mehretu's squares are stand-ins for "squares where political confrontations have taken place, including Tiananmen Square in Beijing, Red Square in Moscow, Plaza de la Revolución in Havana, and Meskel Square in Addis Ababa, where she [Mehretu] was born and spent her earliest years." Mehretu tell us that her paintings are architectural surveys that pluck from both the great masters of figuration and the twentieth century bulwarks of abstraction but, like Perl, I find myself lost in navigating their meaning. Granted, painting need not always articulate meaning as such—sometimes, the success of a painting subsists on a somatic, affective, phenomenological register. But worse yet, I find myself unaffected by Mehretu’s works, which I find close cousins of what Walter Robinson famously called “zombie formalist” painting—i.e., abstract paintings churned out alongside a coeval over-eager art market. Robinson describes “zombie formalist” paintings as follows:

"Formalism” because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting (yes, I admit it, I’m hung up on painting), and “Zombie” because it brings back to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg, the man who championed Jackson Pollock, Morris Louis, and Frank Stella’s “black paintings,” among other things.

However, I disagree that it is Greenbergian medium-specificity that is revived, for Greenberg—contra the (mis)readings unspooled by the likes of Krauss, Fried, and Fer, amongst others—is genuinely a theorist of the affective, as evinced by Greenberg’s notion of “at-onceness”, outlined in “The Case for Abstract Art” (1959). Greenberg here writes:

When a picture presents us with an illusion of real space, there is all the more inducement for the eye to do […] wandering […] the whole of a picture should be taken in at a glance; its unity should be immediately evident, and the supreme quality of a picture, the highest measure of its power to move and control the visual imagination, should reside in its unity. And this is something to be grasped only in an indivisible instant of time. No expectancy is involved in the true and pertinent experience of a painting; a picture […] does not "come out" the way a story, or a poem, or a piece of music does. It's all there at once, like a sudden revelation. This "at-onceness" an abstract picture usually drives home to us with greater singleness and clarity than a representational painting does. And to apprehend this "at-onceness" demands a freedom of mind and untrammeled of eye that constitute "at-onceness" in their own right. Those who have grown capable of experiencing this know what I mean. You are summoned and gathered into one point in the continuum of duration. The picture does this to you, willy-nilly, regardless of whatever else is on your mind; a mere glance at it creates the attitude required for its appreciation, like a stimulus that elicits an automatic response. You become all attention, which means that you become for the moment selfless and in a sense entirely identified with the object of your attention. The "at-onceness" which a picture or a piece of sculpture enforces on you is not, however, single or isolated. It can be repeated in a succession of instants, in each one remaining an "at-onceness"—an instant all by itself. For the cultivated eye the picture repeats its instantaneous unity like a mouth repeating a single word.

Although Greenberg strikes an arbitrary distinction between abstract artworks and figurative artworks in this essay, abstract representations are here taken to stand in an intentional relationship to our automatic emotional responses, where the latter are embodied appraisals initiated prior to subsequent cognitive monitoring. Insofar as Greenberg is uniquely concerned with the abstract artwork, the evoked emotions are in continuity with the properties of the medium’s formal content. Greenberg distinguishes abstract painting and its reified representational substratum on the basis of abstract painting driving home its “at-onceness”—i.e., the stimulus-response that elicits an “automatic”, all-encompassing, selfless sense of identification with the object of our attention. Nevertheless, suspicious readers may take this somatic description to be something of an outlier in Greenberg’s thinking. However, in his 1960s notes from “How Art is Acquired”, Greenberg reinforces this point by underscoring the “surrendering” of “attention” that accompanies our apprehension of “authentic art”. (This reading of Greenbergian affectivity is brilliantly captured in Daniel Neofetou’s recent book, Rereading Abstract Expressionism, Clement Greenberg and the Cold War (2021), which I cannot recommend highly enough). Rather, and I do think Robinson is on to something, “zombie formalist” artworks lack the authenticity that is indexed by the somatic response that the great abstractionists of yore (viz., Malevich, Kandinsky, Mondrian, van Doesburg, the Helhesten/CoBrA artists, Hofmann, Gottlieb, Rothko, Pollock, Still, Lewis, Delaney, Krasner, Motherwell, Newman, Frankethaler, to name just a few)—invited. I shan’t name any names, but there is an unfortunate veering towards flatness and tepidness in much of the abstraction of the past fifty years, with notable exceptions like the late, great French Stygianist Pierre Soulages. This is met by an unfortunate turn towards figuration, recently baptized “New Figuration”, which trades solely on the exhibition-value of the artists’ identity, betraying the autonomy from heteronomy that Trotsky, Rosenberg, and Adorno all recognized.

All of this brings me back to Kwan Jin Oh. Oh is not an abstractionist, proper. Nor if such a figurative artist, proper. That he has not committed to either camp in full is all for the better. Oh makes use of abstraction, in continuity with figuration, bringing elements of both into a latticework that is affectively effective. The affective response I feel from these paintings is, granted, quiet, but is a low, sustained rumble—a peaceful prodding and humming that invokes the very poetry that these aged moon jar vessels, so craftily plucked and imprinted, croon. This shows that there can indeed be a melodious act of intertwining abstraction and figuration. In this case, it is songlike.

(Text by Ekin Erkan)